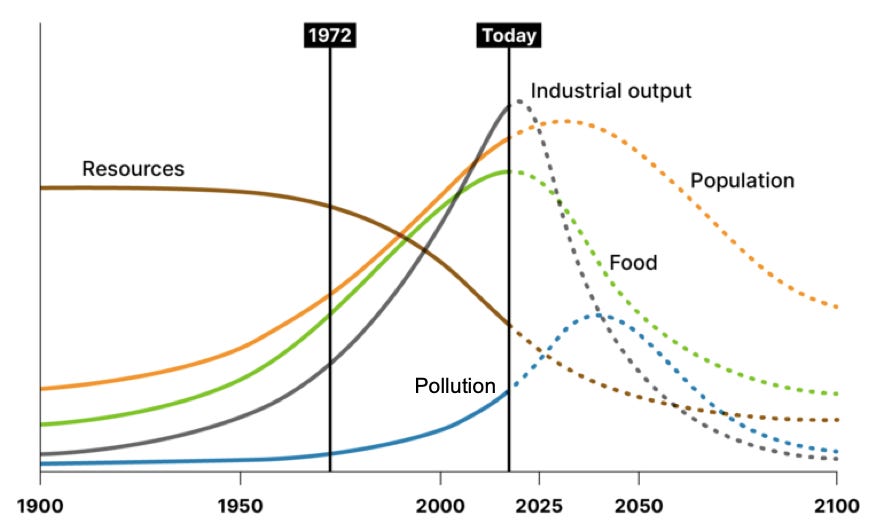

Our world is changing in inconceivable ways. The world our children are growing up in is a world our grandparents could have never imagined. Rarely do we consider the profound implications of what became a buzzword in the beginning of the 21st century: “unsustainable”. Our dependence on fossil fuels, the utilization of violence to settle international conflicts and maintain civil order, industrial-scale agriculture, and even the global financial system: all unsustainable. The book “Limits to Growth” predicted societal collapse back in the 1970s, backed by robust research and scientific modeling. We have yet to refute their findings.

Yet, it’s rare that we as a society face this directly. More often, we behave like the people in the movie “Don't Look Up”, unwilling to look directly at the comet fated to devastate the planet. We are fed media and countless other forms of stimulation—as if designed precisely to distract us from our fundamental mortality and the fragility of our civilization. The Met Gala displays extraordinary opulence while children starve to death in Gaza. Media pundits condemn student protests for being “disruptive” while ignoring the unconscionable violence and the reasonable demands the protestors themselves are fighting for.

Yet, it's hard to blame any of us for turning away from the devastation. The world we’ve known is ending—climate change, social decay, and countless others are changing the world in irreversible ways—how are we to see beyond the current paradigm? Who among us can imagine the future beyond it? Few have actually done so.

Even the student protests are not immune to this criticism. While they accurately highlight the complicity of mainstream institutions related to the state violence overseas—their movements are rife with violence of their own kind. They dehumanize those who don't support their cause while they fail to promote a coherent vision for the future beyond the violence.

Of course, some people do have coherent visions of a peaceful future for the Middle East, though those voices are not the most often heard. Similar dynamics play out in many kinds of activism. The far-left activists who call “defund the police” police their own activities relentlessly. The same people who call for an end to US imperialism engage in the very same tactics of war—framing their own victory as a defeat of the other side.

I have heard some people on the left debate whether or not to call the October 7th attack by Hamas “horrifying”. These are thoughtful people, it seems, who genuinely want to arrive at a proper answer to that. Some very compelling arguments are made as to why not to condemn the Hamas attack—primarily that those of us who live in privileged circumstances have no right to judge the actions of the oppressed.

I have a different take. I don't think we have the right to judge the character of Hamas or other violent extremists for extreme actions taken in desperate circumstances. I, too, have acted out violently in times of desperation and pain. I’m sure you have, too. Though, those actions have never led to a better world. Thus, if we are committed to creating a better world—a world of justice and liberation for all people—violence of that kind must be challenged in all forms. If we cannot agree that it is wrong to murder—regardless of circumstance—we risk losing contact with a spiritually rooted morality and the political dialogue devolves into tribalistic chaos. This is, of course, the current political landscape of the US today.

I agree that the violence between Israelis and Palestinians is asymmetrical. The violence inflicted upon Palestinians by Israelis far outstrips violence in the other direction. Yet, I am working towards peace, thus any act of violence undermines that cause. I denounce the violence of the Israeli government not because they are Israeli, but because of the violence. I denounce the violence of Hamas not because they are Palestinian, but because of the violence.

This is for a simple reason. I want to see a peaceful world. Murdering civilians—no matter what the cause—creates pain, hatred, resentment, and the desire for vengeance. This fuels the forever cycle of violence.

Were I an Israeli Jew attempting to secure the safety of my country would I be peaceful? I don't know. Were I a Palestinian in Gaza living under Israeli siege for over 15 years would I be peaceful? I don't know. I have behaved in verbally violent ways in far less extreme circumstances, so the evidence isn't encouraging. I hope if I was behaving destructively, someone would speak out to stop me.

I recall a class I took in college—Environmental Sustainability 300—I think it was called. We learned a lot about how fossil fuels, land use change, and resource extraction of all kinds have contributed to climate change and threatened the integrity of the planet. We also learned about the economic models that allow for the natural world to be treated like a trash can—entirely outside the purview of the profit-seeking capitalists. It was common in this group to be anti-capitalist. It was common to bear resentment towards politicians, CEOs, and various elites who used their power to consolidate resources rather than heal the planet. Folks were rightfully angry.

Towards the end of the semester, we had a final project—a speech. The premise of my speech was simple. The politicians, the CEOs, the power elites—they too were dependent on the planet for their wellbeing. They, too benefitted from a healthy planet. Zero-sum metrics that portrayed the powerful as villains who must be defeated in order to heal the planet ignored the reality of interdependence (however true it may be that their actions must be opposed). The healthy planet with a restored environment that all of us wanted is a planet we would share with those very people. Ultimately, they would benefit from that victory.

Unsurprisingly, my message was not popular. My speech moved almost no one as far as I could tell. Even my teacher was unimpressed—earning me one of the lowest grades I had received in the class all semester. In hindsight, I do recognize some naive idealism that has been tempered as I've grown. Being on the receiving end of state violence and recognizing just how violent our social systems are has revealed to me that we do often need to fight to achieve justice and systemic change.

Yet, I still hold the same basic views I did then. The real change this world needs will not come merely through violence or defeat of the other. If political victory requires defeat, than peace requires reconciliation that ennobles and includes the needs and humanity of the defeated. Perhaps if that had been done after WWI, we could have avoided the rise of the vengeful Nazi party that initiated WWII.

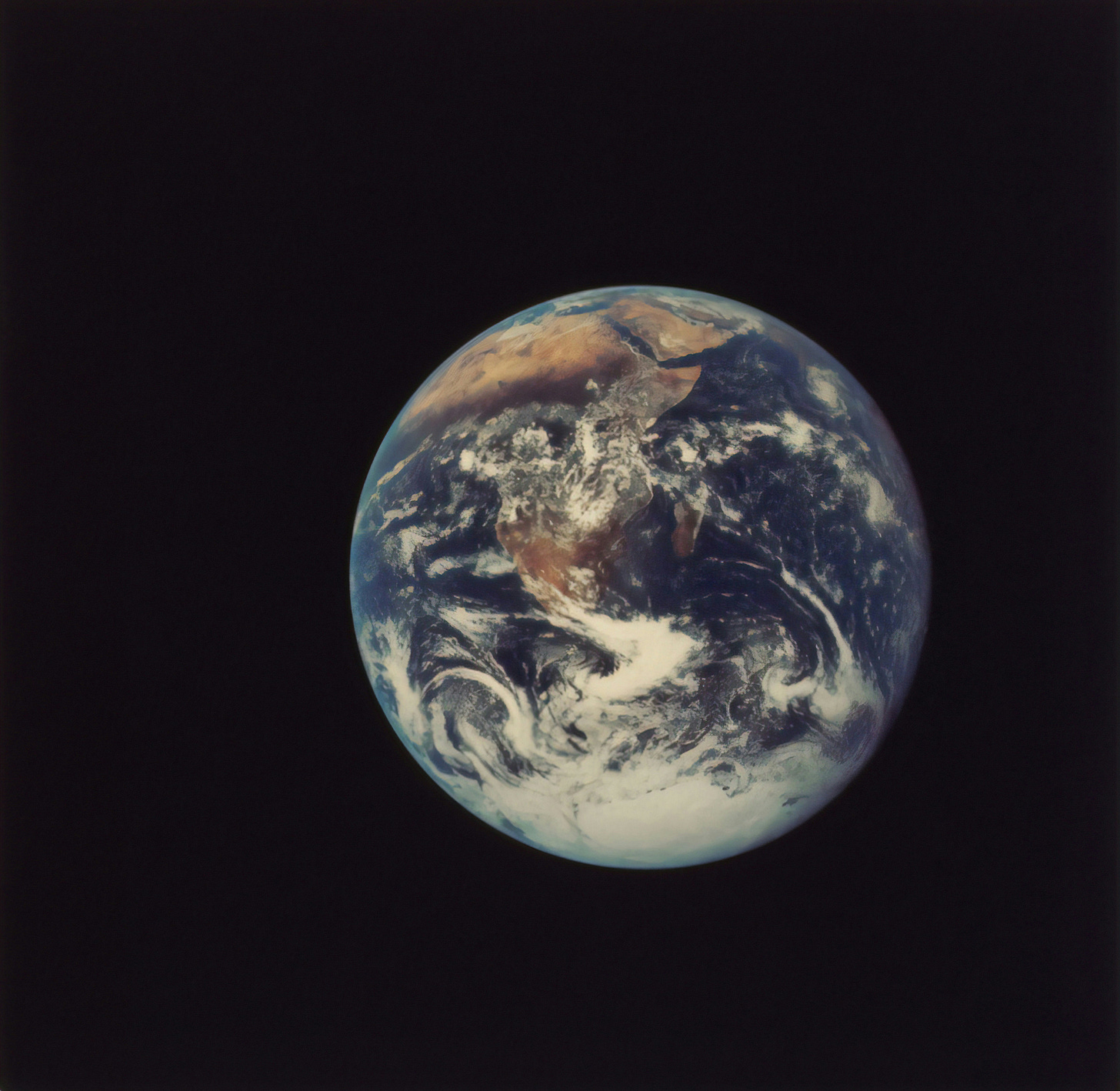

Thus, what we sorely need is a vision of the future that includes all people. That respects all people. That honors all people. That honors the needs and worth of the more-than-human world as well.

I've often wondered how different things would be in the much-conflicted region of the Middle East if it was truly treated like the Holy Land that it is. More than once I've been wracked by waves of grief that the Holy Land has been stained with the blood of countless Palestinians and Israelis over the matter of who gets to control it. If the land was universally honored as sacred, precious, and alive—such acts of violence would be unthinkable. Yet, despite how many people call that land the Holy Land—it's treated much more like a prize or a possession to be owned.

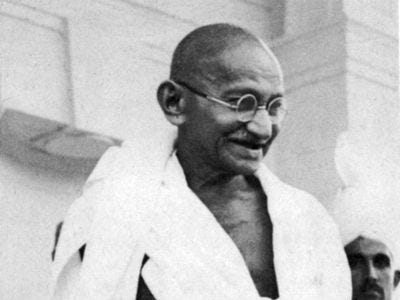

Lately I've been reading a biographical account of Mahatma Gandhi. While he was certainly not a perfect man—severe with his wife and controlling towards his children—he still left an extraordinary mark upon this world. The power of this man, to me, is that he fiercely engaged in the realm of politics founded upon some basic spiritual principles. He was inspired by The Bhagavad Gita and Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. He loved Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy. He inspired vast political nonviolent actions among the Indian people by appealing to spiritual principles (this despite the fact that his followers consisted of Hindus, Muslims, and others). By adhering steadfast to universal spiritual principles, Gandhi was unmoving in his convictions and endlessly generous and compassionate in his approach.

It's not at all hard to see why this would be so revolutionary given the war, imperialism, and racism of his day. Though it is no less revolutionary today.

Spiritual principles of all mystical traditions (be they Christian, Buddhist, or Sikh), converge in similar ways. They extol the virtues of compassion and truth. They reveal the interconnectedness of all life. They speak to an organizing intelligence that flows through all things.

If we truly embodied these principles widely, we would no longer have to fight oil companies that seek to build pipelines under rivers. We would no longer have to fight wars with others in order to feel safe. Such things would be unthinkable in a world where we knew and felt our inherent unity with one another.

Gandhi imagined a politics that would be based not on violence, but on empathy and compassion. I admit that I cannot yet imagine exactly how that world may be. Yet, we are already seeing the collapse of International Law and all else that has governed us until now.

One way or another, a new world will be created. Will it be a world of chaos where the lowest-common-denominator wins a battle for dominion? Or will it be a world where compassion and empathy guide our lives?

The choice will arrive for each of us sooner than we might want to think. Now is the time to practice—to cultivate these deeper qualities. The false illusion of safety forged by the rule of violence has had its day. It is ending. If there is safety to be found in the world beyond what is currently ending—it will only be found by cleaving to spiritual truths.

This is the foundation of the political world I want to live in. The world that is truly best for everyone—the Palestinians and the Israelis, the Republicans and the Democrats, the anarchists and the fascists.

To create that world requires commitment, sacrifice, courage, and faith. It is forged by the actions of today.

No longer will I be pro-Palestinian or anti-anything.

Today I begin working for peace.

I hope you will, too.

Will you join me?

Love this. The part about the speech you made at school reminded me of my own university days, where in my final exam in a course on the Holocaust, I noted that we all have darkness in us, and that none of us can say what we have done if we lived in Nazi Germany during WW2. I also received a very low grade. It's so easy to typecast groups of people as evil, when people exist in circumstances that are beyond our comprehension and experience. I agree that having peace as the goal, regardless of who did what to whom is definitely what is needed.