Hey all! I am back from my adventures in Europe and I am feeling inspired! Let's continue exploring this thread of truth. Bear with me on this one. It’s a bit of a ride!

A few years back I decided to start answering questions on the website Quora. For those who don't know, it's a website where people can ask questions and anyone in the community can answer. During this brief Quora time, I answered a question about how to improve one's intuition. I suggested to this person that all people have intuition or perhaps even psychic abilities. That is, all of us are available to information beyond our typical five senses. We may experience this as flashes of insight, “gut feelings”, or perhaps even revealed to us in dreams. I suggested to this person that the reason that many of us don't experience ourselves as very psychic or intuitive is that we have been culturally conditioned to ignore such messages. “It's only your imagination,” someone might say. Though most of us have probably had the experience of making a poor decision and in hindsight, realizing there was some strong feeling that something was off that we dismissed because it “didn’t make sense”.

Anyway, if you're interested in this, check out the Quora post itself. You’ll have to scroll down a bit. Though my point here is not necessarily to talk about psychic abilities or intuition. Perhaps another day.

The reason I bring this up is because someone recently commented on this post—over seven years after I originally wrote it. My first-ever response to a Quora answer! What did he say?

“Complete and utter nonsense. Pure BS”

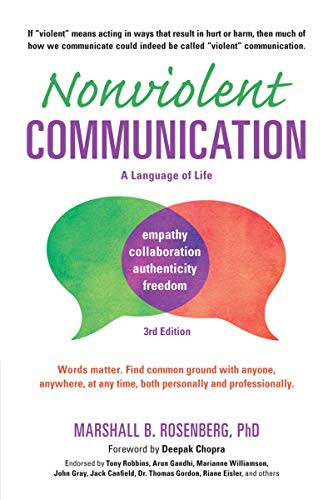

I was surprised and angry upon first reading this. Though, recently I finished reading Nonviolent Communication, which I highly recommend. So rather than ignore him, I decided to become curious about what was going on. Our conversation began several days ago and is still ongoing. Yay, nonviolent communication!

There's a curious discrepancy between the ways we're communicating. I'm trying to be curious about what it is about my post that is so activating for him. So in my exploration, I have brought up the fact that we have different beliefs about the world. His response, though, multiple times, is that we don't have different beliefs about the world. Rather, I'm delusional and he knows the objective facts. He's used the word “fact” multiple times, sometimes preceded by the word “obvious”. Meanwhile, he has referred to my beliefs as “silly”, “delusional”, and several other condemning and derisive things.

Again, my point isn't to suggest that anyone should believe in psychic phenomena. Though, I am curious about his apparent certainty that his worldview is “fact” and my worldview is “delusion.” I'll mention, as well, that I've made no attempts whatsoever to try to convince him of the reality of intuition.

However, I'm struck by his absolute lack of openness. I don’t know with any absolute certainty that psychic phenomenon. He, on the other hand, is absolutely certain that they’re not.

There's a wonderful elder by the name of Stephen Jenkinson, I believe I've mentioned him before. It's fantastic listening to him be interviewed. He will sometimes refuse to answer certain questions, saying things like, “I feel no obligation to accept the assumptions implied by the question.” Often, he seems to inspire some questioning on the part of the interviewer regarding whatever assumptions he/she is bringing into the interview. Perhaps this is what good elders do.

One of the things I've heard him mention before is the way our culture is founded upon some illusion of certainty. We love certainty. We want to absolutely know things. Then act from that knowledge with the confidence and sureness that what we know is right. We go through great efforts to try to glean some certainty about the world. When we don't have it, we try to conjure it. Thus, we pretend to know things with certainty—even when we couldn’t possibly know.

Though, we must ask ourselves. Is there any real certainty? Do we actually know anything to be objectively true?

I think sometimes people perceive me as anti-science. After all, how could one truly love and respect science while believing such outlandish things as psychic phenomena?

I'm not anti-science. In fact, I love science. Though, it seems to me that most people have a profound misunderstanding of what science actually is. People treat it like a fountain of knowledge about the absolute nature of the world. People will say things like, “This is the truth as revealed by science.” I've said this before and I'll say it again. It is against the very nature of science to reveal the truth. That is something it is entirely unable to do.

People sometimes say that the term scientific theory is just jargon for scientific fact. Though, there are no scientific facts—and for good reason.

Science is, essentially, a creative and investigative process. Someone concocts a hypothesis about the world—essentially imagining some law of nature or other such thing. Then studies are devised to test the validity of the hypothesis. If during the course of study, something is observed that violates the hypothesis, it is thrown out. If the observations are consistent with what one would expect if the hypothesis were true, the hypothesis stands. When enough tests and observations are done that corroborate this hypothesis, the hypothesis is codified as a theory: our best working model for reality.

Though that's all it is. A model. It's actually impossible to verify if a given theory is true. Having a scientific theory is like saying, “This is our best guess so far, and nothing has shown us that it’s false… yet.” However, any theory is open to question constantly. The more we learn about the world, the more we refine our theories and hypotheses, hopefully getting to a more and more accurate picture of the world. Though the theories are our creations. There is no such thing as scientific fact.

There was a time in history when the Catholic church ruled much of society in Europe. In these so-called “dark ages”, priests and church representatives were considered to be the authority about what is real and true. The words of the church authorities were treated as gospel. While I can't know what people thought privately, it certainly seems that the public opinion was that what these church authorities said was absolutely true.

Enter the Enlightenment. Suddenly, people were discovering that much of what the church was saying wasn't true. In fact, we didn't need church authorities to tell us anything! We could run our own experiments, observe the world, and utilize the process of rational thought to determine the truth for ourselves.

The Enlightenment, obviously, was an enormous boon for society. It initiated a profound burst of creativity and technological advancement—the fruits of which we stand upon to this day. However, in the early 20th century—while many of our present-day political realities were being formed—many philosophers began to think quite critically about the Enlightenment. It was clear that the Enlightenment improved our material lives. Yet some philosophers, particularly political philosophers such as Leo Strauss, Hannah Arendt, and Isaiah Berlin; think we may have missed the boat. (check out the Philosophize This! podcast to hear more about this—episodes 134-141)

Certainly, we must celebrate that we threw off the shackles of blind obedience to church authorities! However—these philosophers might ask—did we simply trade one master for another? We abandoned the absolute authority of the church but turned to a new absolute authority: reason itself. The crux of the Enlightenment mentality was that rational thought and analysis could reveal to us the true nature of reality—the proverbial face of God.

Of course, the use of reason and science has led to amazing technological advancements. With things like satellites, spaceships, and the device upon which I write these very words—one would indeed be foolish to completely denounce the value of reason. Though, it's a very different stance to say, “Reason and science have led us to the creation of some very useful things,” vs saying, “Reason and science reveal to us the objective reality of the world.” It is the turn towards this second way of thinking that these early 20th-century philosophers seem to think we lost our way.

This is how we traded one master for another. We turned away from the certainty of religious authority and towards the certainty of rationalistic authority. Perhaps, these philosophers suggest, we would have been better off releasing our attachment to any kind of existential certainty at all.

Now, I wasn't alive at the beginning of the Enlightenment. I'm not sure humanity was ready to leap into the existential humility and terror of admitting that there’s much we simply cannot know. Though, it seems to me that we're at a similar juncture at this moment in history. Perhaps we can finally get aboard the boat that we missed back then.

Certainty, in my view, is an intellectual trap. The moment we become certain about any particular thing we believe, we close our minds to any alternatives. We act, blindly, as if this were true. I find this to be extremely dangerous.

This danger may be obvious when different people become equally certain about different particular worldviews. Some people, for example, think that the government shouldn't touch our guns. Some people, on the other hand, think that people shouldn't own guns at all. If people in these two camps feel certain about their particular views, they become deaf to the feelings and concerns of the other side. Then both, in their certainty, come to view the other side as their adversary. The only way to achieve a world based on truth, then, is to defeat in political battle the aims of the other side. Perhaps it would take only one of the sides to say, “Actually, we don't fully know what the answer is, but we want to begin a process of talking about how best to protect our children,” to begin a genuine dialog wherein both sides might be heard.

However, the danger when people largely agree on a particular worldview may be no less severe. Indeed, it may be even more dangerous when an entire population becomes certain about a particular thing. The witch hunts in Europe and the Crusades come to mind. In both cases, it seems there was some cultural certainty regarding some kind of social contagion. In order to purge it, violence was used.

This may seem absolutely barbaric to us now, but imagine this:

You truly believe, deep in your heart that there are evil women out there with dark magical powers. They are secretly plotting to kill you, and your loved ones, and to plunge society into chaos. Of course, you love your family and your kids. You would do just about anything to protect them. In your mind, these evil women aren’t a possibility. They’re an absolute fact. Tell me, what choices do you have? You may cringe at the notion of possibly killing innocent women. Though, you may think that this is a passable risk in order to do what “needs to be done.”

Did you catch it? The insidious nature that this kind of existential certainty creates. When we believe, unquestioningly, in the truth of our own thoughts, we can be led to a conclusion in which there is no other way.

Most recently, our entire planet was engaged in this kind of plague. When Covid was running rampant, we were understandably scared. Perhaps it's when we are fearful that we crave certainty most of all. We want to be safe. We want to know what to do in order to be safe. Thus, seeking certainty is a very natural thing. So, during the pandemic, certainty is what we found.

The television experts and medical authorities told us to mask up, stay at home, and ultimately take the vaccine. I’m not here to argue for or against the effectiveness of these interventions. Rather, what’s notable for me is the way the orthodoxy of this approach seemed to shut down creative exploration of alternatives. People have long been suggesting the preliminary efficacy of ivermectin and doxycycline, for example.

I'm now entering territory where many of your minds may be throwing up red flags. “That can't be true!” It may say. “That's all been disproved!” Perhaps some of it has. Honestly, I haven’t combed the research thoroughly. My point is not to concoct an alternative certainty but to soften any certainty of yours. Kevin Bass in this Newsweek article, says, “I was wrong. We in the scientific community were wrong. And it cost lives.” He is far from the only person saying things like this. (1, 2, 3)

Of course, it’s totally acceptible to be wrong about something. But the consequences of being wrong are far more severe when alternative perspectives are diminished.

What if, during the midst of the pandemic, the medical authorities had said something like this: “This is a massive and unprecedented danger to public health. We advise such and such things, and we hope everyone will continue to be curious about this so we can find out the best response together.” Perhaps then, we would have been more likely to hear about this paper, published in November of 2021 that suggested that the drugs ivermectin and doxycycline; as well as supplements with Vitamin D, Vitamin C, Zinc, and CBD; were demonstrated in various research trials to be promising treatments for Covid. I wonder if more people would have survived if we knew that our survivability would have been increased by simply taking Vitamin D.

Though, there was a sociocultural orthodoxy that overtook our nation and our world during Covid. There wasn't an ongoing process of discovery to determine how best to respond to Covid. There was one identified response that was deemed the correct one very early on in the pandemic. At the height of the pandemic, being vocal about ivermectin on social media was enough to be de-platformed or even banned—even if one was critical of ivermectin. If an open conversation about ivermectin had been permitted, we may have quickly come to an informed conclusion about it. Instead, a spirited area of debate was effectively shut down.

Anyway, before I dive too deep down into the Covid-era rabbit hole, let's all come up for air. My point here is not to suggest a different kind of certainty or orthodoxy regarding the Covid response. I don’t know what would have been the best response. But that’s my point. Nobody really does. At a time of vast uncertainty and widespread terror—it may have been more beneficial to us to live together with the questions rather than fight about the answers. We are tiny creatures living in a vast and complicated world. To assert certainty about much of anything is to obscure tremendous realms of complexity from view.

Let's return back to the event which I started this article with. I'm in a conversation with someone who doesn't believe in psychic phenomena. Though my concern isn't that he doesn't believe it. My concern is that he doesn't recognize his belief as a belief. He has mistaken his belief as a fact. Remember the two boxes in the Inside Out movie I mentioned last time? Well, there it is. He is so taken by the certainty of his belief, he has gone so far as to say directly that it’s not a belief at all, but a fact.

It's hard for me to not, then, think of the hundreds of thousands of years of human cultures in which psychic phenomena, prophetic dreams, and even the sentience of stones were considered to be just the way things were. Even as recently as ancient Greece, powerful kings would travel to Delphi, making profound decisions based upon the prophetic guidance of the oracle there.

Now, it is certainly possible that all these people were simply wrong. Their worldview could have been built upon false assumptions. After all, how long did civilized people believe the Earth was flat? (Although, even the ancient Greeks knew this wasn't true).

However, many anthropologists throughout the centuries have viewed indigenous people as primitive or savage. They were considered unintelligent, superstitious, or even ungodly because of their beliefs in spirits, ancestor communication, and sentient rocks. Yet, this superiority closed us off from ever learning of the world that they knew: the delicate balance and interdependence among all things in nature, the importance of a reciprocal relationship with the Earth, and the knowledge of traditional medicines that we're still only discovering now. It seems to me that our global state of affairs might have been vastly improved had we been willing to learn humbly from these Earth-based people rather than assuming that we knew the world better than them.

Again, it doesn't mean that everything they believed was true. After all, to believe that would be to make the same mistake of the Enlightenment—to trade one type of orthodoxy for another.

Though, if we had been willing to admit that there's a lot that we don't know, we may have been willing to learn from them. If we had admitted that we didn't know the right answer to Covid, perhaps we could have had a much more nuanced response. Had we not believed in the certain evil of medieval witches, perhaps many wouldn't have had to die. If we were to release our attachment to certain political ideologies, perhaps we could cooperate again.

Perhaps, even, if we admitted that there may be mysterious happenings in the world beyond our materialistic worldview—we may be open to possibilities that we can't currently imagine.

I’m sure I’m not the only one who thinks we could use a miracle right about now.

What do you think? Could we benefit from being a little less sure about things? Am I crazy? Both?

I truly would love to hear your thoughts. Feel free to subscribe and leave comments below.